ARTH Courses | ARTH 209 Assignments

Fourth Century Sculpture: the Late Classical

Praxiteles (act. 370-330 B.C.), Hermes with the Infant Dionysos, c. 340-330.

| Praxiteles, Apollo Sauroktonos, Roman copy of original from c. 340-330 B.C. | Possible Hellenistic or Roman bronze copy of the Apollo Sauroktonos in the Cleveland Museum of Art. |

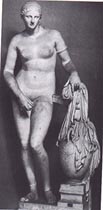

| Aphrodite of Knidos by Praxiteles, Roman copy of an original of c. 340 B.C. 360 degree view of the Aphrodite of Knidos. | |

Pseudo-Lucian, Amores 13-14, 2nd century A.D. presents the following account of seeing the Aphrodite of Knidos:

|

When we had enjoyed the plants to our fill we entered the temple. The goddess is sited in the middle, a most beautiful artistic work of Parian marble, smiling a little sublimely with her lips parted in a laugh. Her whole beauty is uncovered, she has no clothing cloaking her, and is naked except in as far as with one hand she nonchalantly conceals her crotch. The craftsman's art has been so great as to sujit the opposite and unyielding nature of the stone to each of the limbs. Kharikles, indeed, shouted out in a mad and deranged way, 'Happiest of all gods was Ares who was bound for this goddess', and with that he ran as far as he could kissed it on its shining lips. But Kallikratidas stood silently, his mind numbed with amazement. The temple has doors at both ends too, for those who want to see the goddess in detail from the back, in order that no part of her may not be wondered at. So it is easy for men entering at the other door to examine the beautiful form behind. So we decided to see the whole of the goddess and went around to the back of the statue. Then, when the door was opened by the keeper of the keys, sudden wonder gripped us at the beauty of the woman entrusted to us. Well, the Athenian, when he had looked on quietly for a little, caught sight of the love parts of the goddess, and immediately cried out much more madly than Kharikles, 'Herakles! What a fine rhythm to her back! Great flanks! What a handful to embrace! Look at the way of the flesh of the buttocks, beautifully outlined, is arched, not meanly drawn in too close to the bones but not allowed to spread out in excessive fat. No one could express the sweet smile of the shape impressed upon the hips. How precise the rhythm of thigh and calfall the way down to the foot! Such a Ganymede pours nectar sweetly for Zeus in heaven! For I would have received no drink if Hebe had been serving.' As Kallikratidas had made this inspired cry, Kharikles was virtually transfixed with amazement, his eyes growing damp with a watering complaint. |

Two plaques with naked goddesses from Khania in Crete. c. 650 B.C. related to Near-Eastern fertility goddesses.

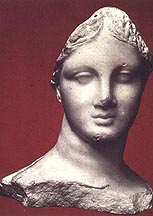

Head from Aphrodite figure from Chios, late 4th century B.C.

Battles of Greeks and Amazons, frieze from the Mausoleum of Hallicarnassus, attributed to Skopas, mid 4th century B.C.

Orgiastic Maenad, attributed to Skopas

Kallistratos (Descriptions 2) writing in the 3rd or 4th centuries A.D. presents the following description of Skopas' Maenad:

| Skopas, moved by as it were some divine inspiration, instilled divine possession into the making of the statue. Why don't I describe it to you the way in which his craft is inspired from above? The statue of a Maenad made from Parian marble had been transformed into a real Maenad. The stone, while staying in its natural form, seemed to escape the laws of stone, for what appeared was really an image, but the sculptor's skill had made the representation a representation of real reality. You would see that the stone that was really hard was softened to give the impression of female flesh, achieving a radiance that got the female just right, and stone which had no power to move displayed knowledge of bacchic revelry, and responded to the god entering within it. When we saw the face we stood speechless, so clearly was perception expressed by one who had no perception, the Dionysiac possession of the Maenad was manifest without there being any possession, and all that the soul displays when stung by madness, all the signs of passion, shone out through the sculptor's skill blended with secret reason. |

Lysippos, Apoxyomenos, Roman copy of an original dating from c. 330 B.C. For 360 degree view of the Apoxyomenos.

Lysippos and Greek Portraiture

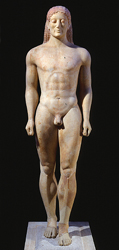

Anavysos Kouros (Kroisos), c. 530 B.C.

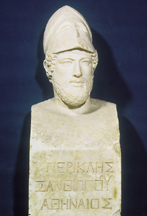

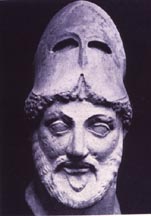

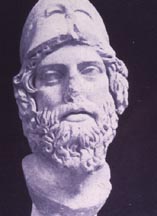

Pericles, copy of a bronze original from c. 440-430 B.C.

A silver stater from the southern Italian city of Metapontion, dated 330-325 B.C. The obverse shows the city's legendary founder Leukippos. It clearly follows the formula of the Athenian strategos portrait like the Pericles portrait..

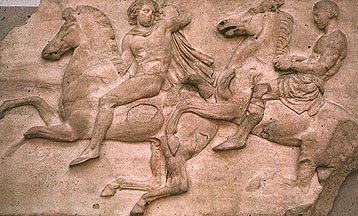

Panathenaic Frieze from the Parthenon

Gravemarker of Dexileos, son of Lysanias from the Kerameikos cemetery of Athens, 394-3. Dexileos died at the age of 20 in the battle of Corinth in 394 BCE.

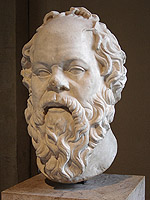

Socrates, Roman copy of an original from the first half of the fourth century BC. Plato in his Symposium, has Alcibiades start his speech praising Socrates compared the great philosopher's look to Silenus, companion of Dionysos and likened to the Satyrs.

Satyrs head antefix from Gela Sicily, early 5th century BC.

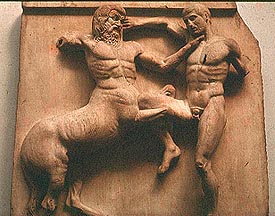

Battle of Lapith and Centaur, from the Metopes from the Parthenon.

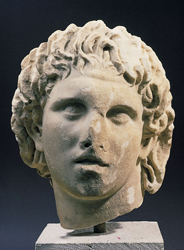

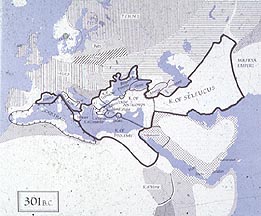

Lysippos, Alexander the Great, c. 330 B.C., copy of the original. Alexander succeeded his father who was assassinated in 336 B.C. From 333 until his death in 323 B.C., Alexander led a remarkable campaign to extend his empire to the borders of India and in the process toppled the old Greek nemesis, the Persian Empire.

Plutarch in his life of Alexander the Great includes the following passage referring to the portraits of Alexander by Lysippos: "So Alexander ordered that only Lysippos should make his portrait. For he alone, its seemed, brought out his real character in the bronze and caught his essential genius (arete). The others, in their eagerness to represent his crooked neck and melting, limpid eyes, were unable to preserve his virile and leonine demeanor."

Silver coin of Alexander the Great with Herakles on the obverse and Zeus on the reverse. To establish a Greek identity, Alexander claimed that he was descended on his father's side from Herakles and on his mother's side from Achilles. The representation of Heracles with the pelt of the Nemean lion covering his head can be compared to the portraits of Alexander with his wild, lion-like hair. Herakles is more regularly shown as a bearded figure. The choice of the beardless figure strengthens the connections to the portraits of Alexander.

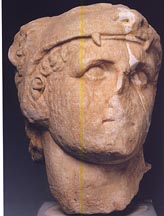

The Head of Telephos in the style of Skopas, from the west pediment of the Temple of Athena Alea at Tegea, third quarter of the fourth century BC- Telephos was the offspring of the rape of Auge, priestess of Athena Alea, by a drunken Herakles. Telephos became the King of Mysia and encountered Achilles in battle when the Greek expedition to Troy landed in Mysia. Telephos was wounded in battle and was healed only when Achilles' own spear touched it in return for a promise to guide the Greeks to Troy. Here he wears the lion skin associated with his father , Herakles. The connections of Telephos to both Herakles and Achilles made him a special model for Alexander the Great. The Lysippos portrait of Alexander is strikingly similar to the Skopas image of Telephos.