Art Home |ARTH Courses | ARTH 209 Home |

Principal Greek and Roman Gods

(adapted from Laurie Schneider Adams, Art Across Time, 2nd ed., p. 142)

| Greek god | Relationship | Role | Attribute | Roman Counterpart |

| Zeus | husband and brother of Hera | King and father of gods, sky. | Thunderbolt, eagle. | Jupiter |

| Hera | wife and sister of Zeus | Queen and mother of gods; women, marriage, maternity. | veil, cuckoo, pomerganate, peacock | Juno |

| Athena | daughter of Zeus, but not of Hera. Sprung from the head of Zeus fully-formed. | war (strategy), wisdom, weaving, protector of Athens | Owl, Armor, shield, gorgoneion (head of Medusa on breast plate) | Minerva |

| Ares | son of Hera and Zeus | war, strife, blind courage | Armor | Mars |

| Aphrodite |

Homer: daughter of Zeus and Dione (a Titan); Hesiod: she sprung from the sea foam that formed around the severed genitals of Uranus. |

love, beauty | Cupid, Eros (her son) | Venus |

| Apollo | son of Zeus and Leto (daughter of the Titans Coeüs and Pheobe); brother of Artemis | solar light, reason, prophecy, medicine, music | lyre, bow, quiver | Phoebus |

| Helios | later identified with Apollo | Sun | Pheobus | |

| Artemis | daugher of Zeus and Leto; sister of Apollo. | lunar light, hunting, childbirth | bow, arrows, dogs | Diana |

| Selene | later identified with Artemis. | Moon | Crescent moon | Diana |

| Hermes | son of Zeus and Maia (eldest daughter of Titan Atlas) | Male messenger of the gods; trickster and thief; good luck, wealth, travel, dreams, eloquence. | Winged sandals, winged cap, caduceus (winged staff entwined with serpents) | Mercury |

| Hades | brother of Zeus and husband of Persephone | Ruler of the underworld | Cerberos (triple-headed dog) | Pluto |

| Dionysos | son of Zeus and Semele (daugher of Cadmus, king of Thebes) | Wine, theater, grapes, panther skin | Thyrsos (staff), wine cup | Bacchus |

| Hephaistos | son of Hera | Fire, the art of the blacksmith, crafts. | Hammer, tongs, lamed foot | Vulcan |

| Hestia | sister of Zeus | Hearth, domestic fire, the family | hearth | Vesta |

| Demeter | sister of Zeus | Agriculture, grain | Ears of wheat, torch | Ceres |

| Poseidon | brother of Zeus | Sea | Trident, horse | Neptune |

| Herakles | son of Zeus and a mortal woman, the only hero admitted by the gods to Mount Olympos and granted immortality. | Strength | Lion skin, club, bow and quiver | Hercules |

| Eros | son of Aphrodite | Love | Bow and arrow, wings | Amor/ Cupid |

| Persephone | daughter of Zeus and Demeter, wife of Hades | the underworld | Scepter, pomegranate | Victoria |

The Great Goddess

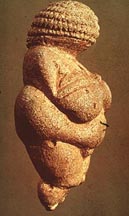

The "Venus of Willendorf", c. 30,000-25, 000 B.C., Paleolithic (see the webpages constructed by Christopher Witcombe dedicated to the Venus of Willendorf)

Preceding the introduction of the patriarchal system of male sky gods, early Europe was dominated by the so-called Great Goddess, a powerful, creative force who through parthenogenesis (conception without sex) gave birth to the universe. She was the source of the great cycle of existence --life, death, re-birth. The Great Goddess appears in mythologies from all over the world:

| Greek | Gaea and Demeter |

| Roman | Ceres, Tellus, and Terra Mater |

| Egyptian | Isis |

| Sumerian | Inanna |

| Babylonian | Ishtar |

| Norse | Nerthus |

The Great Goddess unites opposites within herself: light/ darkness, upper and lower worlds, birth-death-and re-birth. She is both terrifying and beneficent.

See Chris Witcombe's essay on the Minoan Snake Goddess.

The so-called Snake Goddess from Knossos possibly presents the Great Goddess as she was conceived of within Minoan culture. We need to be careful not to read into the snakes held by this figure malevolent forces associated with serpents in the stories like the Garden of Eden and Medusa, that dominate in western culture. The serpent is a totem of the cycles of life, death and rebirth and the seasons. It is the connection to the fertile earth and to the underworld. It also symbolizes immortality as it was thought to shed its skin indefinitely.

The unity of the Great Goddess becomes divided in Greek mythology. Many scholars argue that this division occurs with the introduction of a new culture and religious imagination. Indo-Europeans like the so-called Dorians who apparently invaded the eastern Mediterranean during the end of the second millenium introduced the male sky gods and a much more militaristic culture.

The Olympian gods were ultimately descended from Gaea. According to Hesiod's account of the creation of the universe presented in his Theogony, Gaea along with Tartarus and Eros, was born from Chaos, or at the same time. Without a mate she parthenogenetically bore Uranus (sky), Ourea (mountains), and Pontus (sea). With Uranus, Gaea gave birth to the Titans and Cyclopes. Gaea encouraged Cronus, the eldest Titan, to take a sickle and castrate his father Uranus. Cronus through Rhea became the father of the eldest Olympian gods (Zeus, Hera, Demeter, Hestia, Poseidon, and Hades). In turn, Zeus, the youngest son of Rhea, overturned his father Cronus. Although Gaea had encouraged the elevation of Zeus to king of the Olympians, she ultimately turned against him. She set her offspring the monster Typhöeus and the Giants against Zeus who ultimately prevailed. In Greek mythology, the direct off-spring of Gaea become identified as chthonic forces (from the earth) that become subdued by the Olympians and their followers.

This succession myth and the ascendance of Zeus and the Olympian Gods over the chthonic powers of Gaea and her off-spring echoes the introduction of the patriarchal Indo-European sky-gods into the Mediterranean world and the subordination of the Great Goddess. Scholars examining the remains of Minoan culture have wondered whether it was a matriarchal society. There is no certainty to this conclusion, but for the historical period of Greek culture extending from at least the eighth century B.C. matriarchy represented the opposite of everything that was Greek, civilized, and "normal." Matriarchy was posited as the horrific and chaotic alternative to patriarchy and thereby served as a tool to explain and validate patriarchal institutions, customs, and values.

With the supremacy of Zeus and the other Olympian gods established, Gaea's position is eclipsed. Demeter, the sister of Zeus, incorporates many of the aspects of the Great Goddess, while the different functions of Gaea are divided among goddesses. Under the Olympian Gods, earth and heaven are split eternally. In myth heroes and gods are created to dominate and subjugate the female and natural forces over and over again in various forms, the most common of them being gigantic snakes and serpent monsters. The chthonic identity of the Great Goddess becomes associated with powers of darkness, chaos, and death that need to be subdued by the Olympian gods. What had been cyclical with the Great Goddess becomes cut so that instead of being associated with the cycle of life, death, and regeneration, she becomes identified with the negative functions.

|

See Chris Witcombe's essay on the Minoan Snake Goddess. |

A comparison of one of the large number of representations of the story of Perseus Medusa from Archaic Greek art to the Minoan Snake Goddess illustrates the profound change that occurred with the supremacy of the Olympian Gods. A striking aspect of the Snake Goddess is her frontality combined with her hypnotic stare. The power of this stare was probably intended to strike the original viewers with intense religious feelings of of terror and awe. This expression transcends categories of good and evil. On the other hand, it was the sight of the "terrible" visage of Medusa that would turn men into stone. The powerful gaze in the Minoan work becomes entirely negative and demonized and something to be overcome in the figure of Medusa. Perseus, the son of Zeus and the mortal Danae, slays Medusa with his sword, and thus he destroys the terrifying chthonic powers of the female (for more on Medusa see the paper by Alicia Le Van).

The following excerpt from Bullfinch's Mythology illustrates how the demonization of Medusa persists into our modern imagination:

| Medusa was a terrible monster who had laid waste to the country. She was once a beautiful maiden whose hair was her chief glory, but as she dared to vie in beauty with Athena, the goddess deprived her of her charms and changed her beautiful ringlets into hissing serpents. She became a cruel monster of so frightening an aspect that no living thing could behold her without being turned into stone. All around the cavern where she dwelt might be seen the stony figures of men and animals which had chanced to catch a glimpse of her and had been petrified with the sight. Perseus, favored by Athena and Hermes, the former of whom lent him her shield and the latter his winged shoes, approached Medusa while she slept, and taking care not to look directly at her, but guided by her image reflected in the bright shield which he bore, he cut off her head and gave it to Athena, who fixed it in the middle of her Aegis. |

| The story of Medusa has reemerged in poststructuralist literary theory. Hélène Cixous in 1971 published an influential essay entitled "The Laugh of Medusa." For this see the discussion on the webpage entitled Helene Cixous' "The Laugh of the Medusa". |

Web Resources:

Classical Myth: The Ancient Sources: This site draws together the ancient texts and images available on the Web concerning the major figures of Greek and Roman mythology. Although concentrating primarily on ancienct sources and illustrations, some Renaissance images have been included.